Saturated in Fiction: Consensus Reality as a Web of Stories

From entertainments to the stories we live

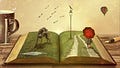

If birds fly and spiders spin webs, people tell stories.

We line up outside the movie theater to watch tales light up the big screen or we binge countless sagas on Netflix. We read reviews of these stories that spin narratives about how the film or television show fits into the larger cultural narrative. And we tell ourselves stories about why we like or dislike this or that drama.

Stories are as vital to us as the air we breathe. Indeed, according to Jonathan Gottschall’s book, The Storytelling Animal, we spend more time in fictional worlds than in the real ones. Popular culture is full of entertaining stories, of course, from novels to movies, operas, video games, songs, and comic books. Then there are the religious myths, the corporate media narratives, and the political party propaganda.

We tell stories around campfires and we gossip, selecting a tidbit to pass along to our network of friends and associates, often exaggerating the story in the retelling until the initial event is turned into a legend. Similarly, we confabulate to fill in missing parts of our personal history or to burnish memories as we reincorporate them when we age. Even when we sleep we dream, and when we’re awake we’re often lost in daydreams, taking a break from the daily grind of weaving our primary self-narrative, our inner monologue that bestows on us the starring role.

As Gottschall says, “Neverland is our evolutionary niche, our special habitat,” and he sets out an evolutionary explanation of the function of story-telling. According to Gottschall, we simulate counterfactuals in our minds and with language, to avoid having to risk personally testing various possible courses of action. Moreover, he argues, we tell stories to capture each other’s curiosity, by way of conveying a moral lesson to help us cooperate and discourage destructive behavior.

But Gottschall’s evolutionary explanation only takes us so far because we’re not slaves to evolutionary functions. We exapt the biological effectiveness of our traits, bending them to our will and assigning them new purposes to suit our artificial environments that have largely replaced the formative wilderness in which we evolved.

Concepts as stock characters

Indeed, it’s easier to ask when we’re not engaged in some form of story-telling. What would it look like to tell the pure, nonfictional truth? After all, concepts themselves are only models, meaning they’re simplifications and idealizations that usefully leave out information we deem irrelevant or insignificant.

We can confirm that by comparing the concept of a dog, say, with a generalization, we’d be more inclined to think is fictional, such as a racist one. A white supremacist’s concept of African Americans is discriminatory in that the racist judges the black person not according to her merit but based on her membership in a class or a “race,” and this judgment carries a value assessment.

Alas, all nonracist concepts operate in the same way. When you encounter a dog for the first time, you think “dog,” which means you generalize about that animal, picturing in your mind only certain features conventionally associated with that species. When we learn the concept of “dog,” we learn that these animals are pets that have four legs and that bark, wag their tails, poop in the streets, and so on.

It’s the same with our concepts of tables, houses, rocks, trees, clouds, and everything else we understand. All concepts are generalizations and also prejudgments and stereotypes. Moreover, there are no morally neutral concepts, apart from the robotic ways of thinking produced by certain antisocial personality disorders. Our concept of dogs, for example, uses the euphemism of “pet” to mean “slave.” Tables, we assume, are good because they’re more useful than trees or because their steel legs are better than the raw iron and carbon they’re made of, or because the plastic is fine since it brings down the price, even though this material will end up in a landfill.

Our mental generalizations, which are ubiquitous in our understanding of anything, are useful as instruments, as ways of reducing possibilities and forming maps to help us navigate the world. Thus, our thoughts are almost always implicitly human-centered and self-serving.

The difference between racism and concepts, in general, is that some people are on the receiving end of racist generalizations, whereas most concepts target things in the environment other than people. Of course, racist generalizations can also be misleading and based on faulty information, but all concepts are misleading to some degree because all of them leave out some details.

We lack the memory power to understand the ins and outs of every phenomenon we encounter, so we have to simplify. Racists simplify at the expense of certain foreigners, often doing themselves a disservice as their narrow-mindedness turns them into loathsome bigots. But our anthropocentric concepts may likewise be doing our species a disservice, by fueling unsustainable economic growth and the despoliation of the biosphere.

Concepts may be adequate for our purposes, but they’re nothing like mirror reflections of what they’re supposed to represent. There is no magic word that names the essence of a thing, without the word being part of an arbitrary system of signs or symbols that has nothing to do with the referent. Our concepts are human tools and our species is an accidental excrescence in a universe that’s perfectly indifferent to our agendas.

While concepts aren’t fictional narratives in themselves, they’re caricatures or stock characters, as it were, that figure in the stories we tell ourselves with our thoughts. If that’s so and the full truth of anything would have to take into account that thing’s relation to everything else, no pure truth, strictly speaking, has ever been uttered.

The success of science

We’ve always simplified, even in scientific theorizing that employs models and ceteris paribus laws. The latter are generalizations that assume a counterfactual state of affairs, namely the scenario in which some process can unfold in a vacuum without interfering with background circumstances and systems. We say, “All things being equal, X causes Y,” which means, “Assuming a world in which X is left alone to do its thing, X would probably lead to Y.”

Of course, in such a vacuum, X would never have developed in the first place and no one knows what X would do if X were deprived of any background in which to operate, that is, if X were placed in pure nothingness. Even space is full of subatomic happenings, but if we’re interested in understanding an aspect of X, we can ignore that background and any other condition we deem to be unrelated to X or to be noise compared to what interests us about X.

Still, the purpose of science is to explain empirical facts, not to tell stories, and contrary to once-fashionable, all-embracing “postmodern” cynicism, science succeeds in explaining how nature works, at least compared to other kinds of discourse. But the point is that this success of science is a difference in degree, not in kind.

Science tells us what’s probable or necessary, not because scientists ever arrive at absolute, pure nonfictional truth, but because scientific generalizations are carefully designed to prune away as much human bias as possible. In so far as they’re informed by experiments, scientific concepts are still humanistic and instrumental, but they’re also impersonal and objective. Science is done to empower our species at the rest of the world’s expense, but scientific explanations aren’t overtly parochial, emotive, or value-laden, compared to unscientific narratives.

The point of techniques

Perhaps the only area of human behavior that isn’t saturated with fiction is our use of techniques. In our professions and daily activities, and in everything from blacksmithing to farming, hunting, medicine, warfare, art, and sports, we suppress our free will in imitation of nature’s automated, mindless processes.

We optimize our attempts to achieve some purpose, using methods, building up skills, and acquiring know-how or technical expertise. To excel at some task we have to learn how the relevant system works, which means we apply our proto-scientific, critical faculties, dispensing with hype and prejudices until we’ve mastered the process and could write a field manual on it.

Even here, however, fiction enters through the backdoor because techniques are always means of achieving some purpose, and our bedrock purposes are typically faith-based, idealistic, and justified with stories rather than any mere list of facts. We learn how to play baseball because we want to have fun and we think the best life is a happy one — which is a lesson taught to us mainly by stories. Or we learn to play that sport because we want to become a professional athlete since we idolize rich and famous people — which again would be a lesson taught to us mainly by stories in popular culture.

As the philosopher David Hume pointed out in his formulation of the problem of induction, even our expectations of what’s likely to happen in the future are never strictly empirical but are motivated by an optimistic habit. We become accustomed to a natural pattern we perceive, so we expect the factors involved are necessarily connected or that they’d always interact in the same way under similar circumstances.

Once again, we presume as much because of the cultural impact of religious stories since most of us are encouraged to think a benevolent deity designed the world and wouldn’t want to confuse or mislead us. Alternatively, we trust in the progressive power of human reason to make sense of our environment, and that trust is due to our uplifting, self-centered inner monologues that collectively add up to the narratives of anthropocentrism or secular humanism.

The stories we live

We tell so many stories because that’s how we lend meaning to objectively meaningless events. Science tells us how things work but not what they’re for, what they should mean to us, or what we should do about them. That’s where fiction comes in because something’s value isn’t found in the physics or the thing’s natural role. Natural events happen with the regularity that we can discern, but the natural order of those events is as cold, impartial, and inhuman as the blackness of outer space.

Full, philosophical understanding includes a reason to go on living despite that fundamental absurdity or meaninglessness. So we take those objective explanations and fold them into a broader fiction or “worldview.” If an objective event is like the spam at the back of the fridge, the event’s fictionalization is the secret sauce we add that makes any old food more palatable.

Perhaps, then, we should be more deliberate about assessing stories in light of aesthetic criteria. We might discard stories if they’re clichéd or they lack artistic vision. This is easily done with popular entertainment but is oddly distasteful in the genres of religion, politics, or our personal narratives since those latter kinds of stories are meant to be nonfictional.

More precisely, those stories are mesmeric, meaning we keep no distance between them and us, as it were; we live those stories, suspending our disbelief in them not just temporarily, as when we immerse ourselves in a novel, but permanently. The difference between the psychotic individual who thinks he’s Jesus or Napoleon, and the average Westerner who considers herself a Christian, a liberal, or a consumer is that the former hallucination is disconnected from the mass delusions of society, whereas the latter one is socially affirmed and detached only from all of objective reality.

We’re able to suspend our disbelief in these less trivial, life-sustaining fictions until we enter into the Faustian bargain and are tragically inclined to reflect philosophically on them. At that point, we realize that these theologies, ideologies, and biased memories are essentially fictions that have captured not just our imagination but our public and private identities.